ISL_Chapter6_Linear Model Selection and Regularization

Written on February 14th, 2018 by hyeju.kim

Chapter 6. Linear Model Selection and Regularization

to improve simple linear model, not using least square methods

-

prediction accuracy

if n»p, low variance

if n is not much larger than p, a lot of variability

if p>n, infinite variance

by constraining or shrinking the estimated coefficients, we can often substantaiially reduce the variance at the cost of a negligible increase in bias

-

Model Interpretability

excluding irrelevant variables from a multiple regression model through feature selection or variable selection

-

Alternatives to least squares method

1) Subset Selection

2) Shrinkage

3) Dimension Reduction

6.1 Subset Selection

6.1.1 Best Subset Selection

- computational limitations

6.1.2 Stepwise Selection

Forward Stepwise Selection

Unlike best subset selection, which involved fitting 2p models, forward stepwise selection involves fitting one null model, along with p − k models in the kth iteration, for k = 0, . . . , p − 1. This amounts to a total of $1 + \sum_{k=0}^{p-1} {p−k} = 1 + \frac{p(p+1)}{2}$ models.

- n < p

Backward Stepwise Selection

- n > p

Hybrid Approaches

forward selection + bacward elimination

6.1.3 Choosing the Optimal Model

-

Two ways of estimating test error rate

-

indirectly estimate test error by making an adjustment to the training error to account for the bias due to overfitting

-

$C_p$ : the lower, the better

-

AIC : the lower, the better

- proportional to $C_p$

-

BIC: the lower, the better

- a heavier penalty on models with many variables

-

Adjusted $R^2$ : the higher, the better

-

-

directly estimate the test error, using either a validation set approach or a cross-validation approach

-

Validation and Cross-Validation

-

computational development -> possible

-

if flat -> repeat -> would change

-

one-stamdard-error rule

first, calculate the standard error of the estimated test MSE for each model size, and then select the smallest model for which the estimated test error is within one stardarad error of the lowest point on the curve

if more or less equally good, choose the simplest model

-

-

-

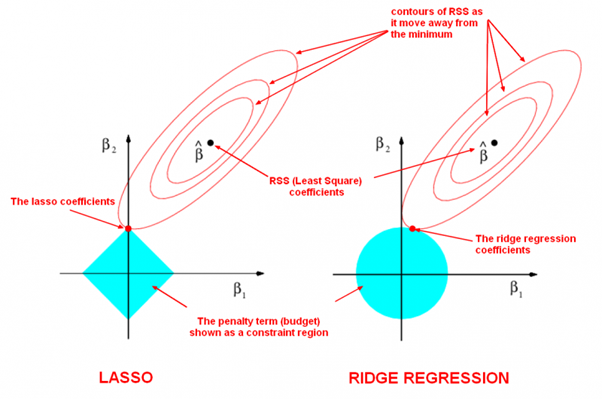

6.2 Shrinkage Methods

- shrinks the coefficient estimates towards zero. -> reduce their variance

- two types of shrinkage methods

- ridge regression

- lasso regression

6.2.1 Ridge Regression

ridge regression coefficient estimates $\hat{\beta}^R$ are the values that minimize

-

$\lambda$ : tuning parameter

-

the second term, $\lambda\sum_j\beta_j^2$, called a shrinkage penalty, is small when β1, . . . , βp are close to zero

-

- λ = 0, the penalty term has no effect.

- λ→∞, the impact of the shrinkage penalty grows, and the ridge regression coefficient estimates will approach zero.

- selection of $\lambda$ critical -> 6.2.3

-

do not shrink the intercept term because if centered, for example, $\hat{\beta}0 = \bar{y} = \sum{i=1}^{n} {y_i/n}$

-

$X_j \hat{\beta}_{j,\lambda}^R$ will depend not only on $\lambda$, but also on the scaling of the jth predictor. * you need to standardize the predictors *

-

the number of variables $p$ is a almost as large as n, or p >n

-> a small increase in bias and a large decrease in variance

6.2.2 The Lasso

-

Ridge regression disadvantage

The penalty $\lambda \sum{\beta_j^2}$λ in (6.5) will shrink all of the coefficients towards zero, but it will not set any of them **exactly to zero (unless λ = ∞). **-> it can create a challenge in model interpretation in settings in which the number of variables p is quite large.

-

The lasso coefficients, $\hat{\beta}_{\lambda}^{L}$ minimize the quantity

$l1 penalty(l2penalty-ridge)$

-

variable selection

-

yields sparse models

-

Ridge and Lasso, which one is better?

can be concluded by cross-validation -> also selecting the tuning parameter $\lambda$

6.3 Dimension Reduction Methods

-

All dimension reduction methods work in two steps

- the transformed predictors $Z_1, Z_2, … , Z_M$ are obtained

- the model is fit using these M predictors

*the selection of the $φ_{jm}$s can be achieved in different ways

- principal components

- partial least squares

6.3.1 Pricipal Components Regression

- dimension reduction technique for regression

- unsupervised

An Overview of Principal Components Analysis

-

the first principal component direction of the data is that along which the observations vary the most.

& the first principal component vector defines the line that is as close as possible to the data( contain the most information of data)

The idea is that out of every possible linear combination of pop and ad such that $φ_{11}^2 + φ_{21}^2 = 1$, this particular linear combination yields the highest variance: i.e. this is the linear combination for which $Var(φ_{11} × (pop − \bar{pop}) + φ_{21} × (ad − \bar{ad}))$ is maximized.

The values of $z_{11}, . . . , z_{n1}$ are known as the principal component scores

-

second principal component $Z_2$ is a linear combination of the variable that is uncorrelated with $Z_1$

orthogonal

The Principal Components Regression Approach

construncting the first M principal comopoents, $Z_1,…, Z_M$, and then using these components as the prpedictors in a linear regression model that is fit using least squares.

- effective when the first few prinicipal components are sufficient to capture most of the variation in the predictors as well as the relationship with the response

- not feaure selection. a linear combination of all p of the original features

- the number of principal components, M, is typically chosen by cross-validation.

- standardizing would be recomendded(high variance variables tend to play a larger role)

- if the vraibles are all measured in the same units (say, kilograms, or inches) -> standardization not needed

6.3.2 Partial Least Squares

- supervised-> to identify new feaure that not only approximate the old feaures well, but also that are related to response -> find direction that explain both the response and the predictors

- standardize predictors and response

- PLS computes the first direction Z1 by setting each φj1 in (6.16) equal to the coefficient from the simple linear regression of Y onto Xj . One can show that this coefficient is proportional to the correlation between Y and Xj. Hence, in computing $Z_1 = \sum_{j=1}^{p}φ_{j1}X_j$, PLS places the highest weight on the variables that are most strongly related to the response.

- second PLS direction: regressing each variable on $Z_1$ and taking residuals. then compute $Z_2$ using this orthogonalized data

- popular in chemometrics field

- reduce bias, increase variance

6.4 Considerations in High Dimensions

6.4.1 High-Dimensional Data

n « p (or p slightly smaller than n)

6.4.2 What Goes Wrong in High Dimensions?(least squares)

- few observations -> perfectly fit the data

- As number of variables increase, $R^2$ tends to increase to 1 and training MSE decreases to 0.

6.4.3 Regression in High Dimensions

- the curse of dimensionality

6.4.4 Interpreting Results in High Dimensions

- regression models in high- dimensional setting

- problem of multicollinearity

- can just say the model is one of many possible models

- train MSE , p-values, $R^2$statistics, … other traditional measures should not be used

- test MSE, or cross-validation errors should be used instead